There was speculation over whether another uprising was brewing in the West Bank, even before the Hamas attacks on Israel in October.

Frequent raids by the Israeli army, emboldened by a hard-right Israeli government – following deadly attacks by Palestinians, and violent attacks on Palestinians by settlers – had already increased pressure on Palestinians there.

Since the war in Gaza, those pressures have spiralled: Israeli raids into West Bank towns have become more frequent and more forceful, and many families are suffering economically after Israel withheld tax revenues used to pay public servants in the West Bank, and banned Palestinian workers from entering Israel too.

There is anger at almost 20,000 Palestinians killed in Gaza, and support for Hamas is rising.

But despite all this, calls by the armed group for an uprising in the West Bank over the past couple of months have come and gone.

Popular mood

Support for Hamas – and armed resistance more generally – has risen sharply since the war in Gaza began.

An opinion poll by the Centre for Policy and Survey Research in Ramallah found that support for Hamas in the West Bank had more than tripled. Meanwhile, support for the West Bank’s ruling party, Fatah, had dropped significantly. More than 90% of respondents thought Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas should resign.

But it seems that support for armed resistance, and disillusion with politics, is not translating into action on the ground.

Since the war began, weekly demonstrations have been held in West Bank cities. The slogans chanted there are against Israel – but also against the Palestinian Authority. But they’re usually held in city centres where there is much less risk of confrontation with Israeli soldiers, rather than at checkpoints – as happened during the last Palestinian uprising in the early 2000s.

And the numbers turning out for these weekly demonstrations are smaller than they were during previous moments of tension.

“People hesitate to come when Hamas calls for demonstrations, because there is a clear security price to be paid from the Israeli response,” said Raed Debiy, a political scientist and youth leader in Fatah.

But they also don’t come when Fatah calls for them, Debiy says, because “people have lost hope in political parties”.

Hamas

As the actions of Israel’s army in the West Bank have become harsher, and the Palestinian security services more efficient, many people fear that becoming an active member of a militant group could make them a target for arrest or assassination.

More than 270 people have been killed by Israeli forces in the West Bank since Hamas attacked Israel on 7 October – including 70 children – according to the UN. That’s more than half the total number killed this year.

Four Israelis – including three from the armed forces – have been killed by Palestinians there in the same period.

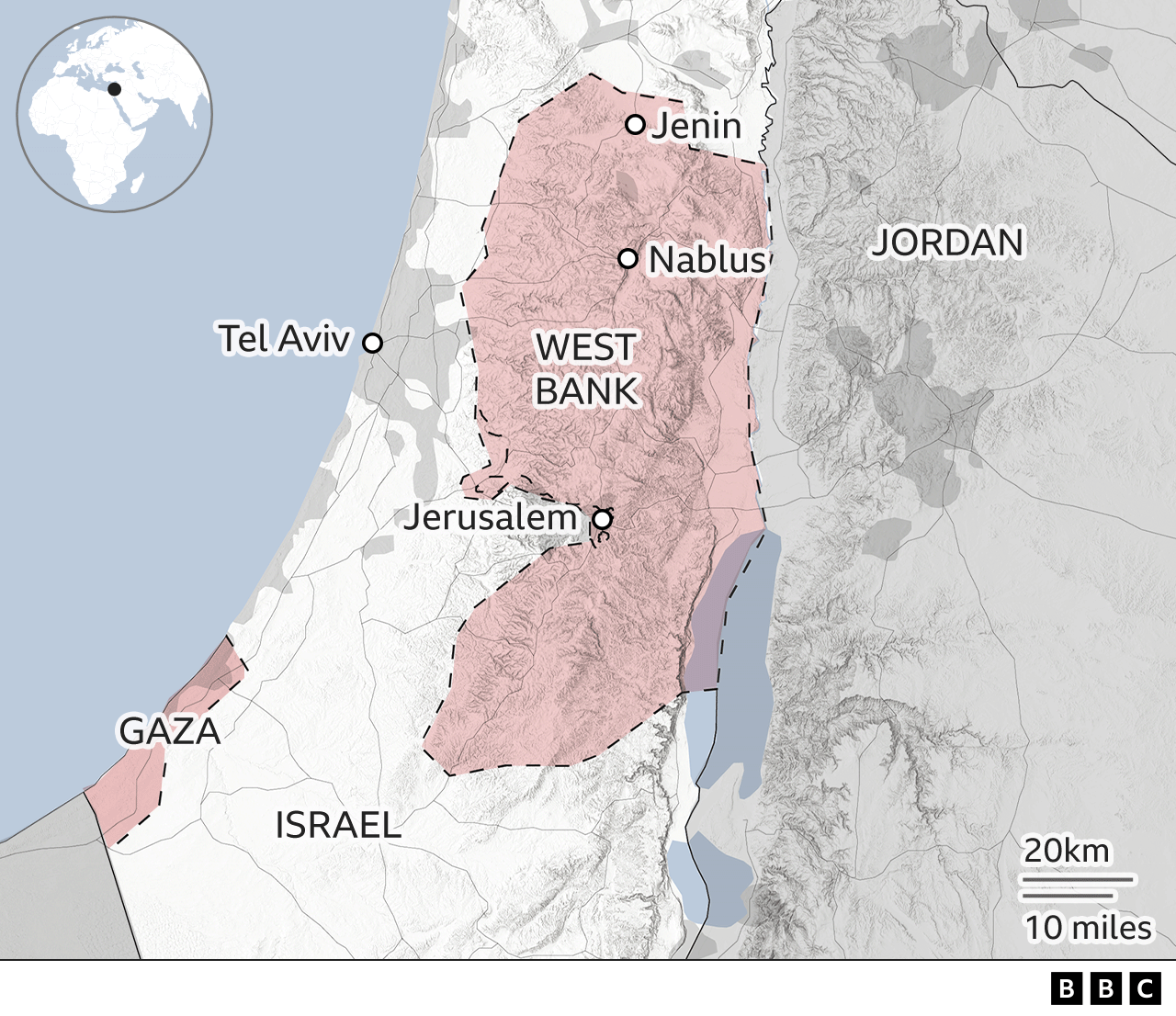

An operation to arrest Palestinian gunmen in the Jenin refugee camp this week lasted several days, with frequent bursts of heavy gunfire, rocket attacks and air strikes. Hundreds of people were detained, with 60 of them handed over to the security services for further questioning.

The Israeli army has also been trying to destroy infrastructure used by armed groups.

This time, it claimed to have found more than a dozen underground tunnel shafts in the camp, as well as facilities for making explosives and “observation control rooms” to monitor Israeli forces.

One young man from the camp, who was among those detained this week and released after questioning, said the reason people ignored calls by Hamas to rise up in solidarity was that the group did not supply the West Bank with enough equipment to fight the Israeli army.

“Hamas in the West Bank has not done a good job of organising itself over the last decade,” said Khalil Shikaki, head of the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research in Ramallah.

“The Israelis have been arresting a lot of their members. Hamas is just incapable right now in the West Bank of mobilising and organising an eruption of violence that would be sustainable.”

But previous uprisings here did not rely on Hamas. The second intifada (uprising), which began in 2000, was led by members of the West Bank’s ruling party, Fatah.

The role of Fatah

The current leader of Fatah, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, is widely seen as trying to avoid an escalation in violence against Israel – a major shift in position from his predecessor, Yasser Arafat.

His security services co-operate with Israel to arrest members of armed groups – something that is widely criticised by Palestinians.

Sabri Saidam, a member of Fatah’s Central Committee, denies that the party’s position is at odds with public feeling in the territory, or that the Palestinian Authority (PA) is somehow avoiding a fight.

“To say that Fatah is in control and keeping the calm, [it’s] as if you are hinting that there is a forceful implementation of a state of calm,” he said. “Nobody is forcing anything on anyone.”

“People in the West Bank know that Netanyahu is throwing down bait, through persistent attacks every night against the people of Palestine regardless of their political affiliation – because he wants to provoke the Palestinians into a confrontational mood that he will use as an excuse to escalate the situation.”

The US is pushing Israel to allow a “revitalised” PA to govern Gaza once the war there ends. Israel has so far said it will not consider it.

But the chance to govern a unified Palestinian bloc for the first time since 2006 is another incentive for the Fatah-dominated PA to prove its credentials and stop the situation in the West Bank from spiralling out of control.

“It’s very clear that Fatah don’t want any intifada,” explained Raed Debiy, the party youth leader. “They are still very keen to keep the status quo. But the grassroots of Fatah will not be controlled forever. How can you stay silent under daily assassination, daily invasion, daily violation of settlers – this will definitely lead to explosion.”

Possible sparks

In 2000, the spark for the second intifada was a visit by then-Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon to a contested holy site in Jerusalem, known to Muslims as the al-Aqsa compound and to Jews at the Temple Mount.

Sharon’s visit happened amid smouldering Palestinian frustration at the failure of the Oslo peace process – and, Dr Shikaki says, was “exploited” by Fatah’s young guard to launch the uprising.

A small event like this could still trigger something significant, but the situation has shifted since 2000.

Now, far-right ministers in the Israeli government visit the compound, and make inflammatory claims about Israeli control of the site, without triggering a major response – at least not in the West Bank.

“We told the American administration many times that the pressure would definitely lead to some sort of reaction,” said the senior Fatah leader, Sabri Saidam. “But no-one anticipated that the reaction would come from Gaza.”

Where the West Bank goes from here depends partly on what follows the war in Gaza.

That transition is likely to be a precarious time for the West Bank, with hopes of a unified Palestinian leadership – possibly opening the door to talks on a future Palestinian state – clashing with the opposition of Israel’s Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu.

And lifting restrictions imposed by Israel after the attacks – separating Palestinian and settler vehicles on some roads, for example – could prompt a spike in friction.

But a sustained uprising, of the kind seen two decades ago, will likely require a change in the policy of the West Bank’s main political movement – and possibly even a change in its leader.

“It seems Fatah remains critical for an uprising to happen,” Dr Shikaki told me. “And as long as Fatah and the security services are not directly involved in the preparation for such an intifada, it seems highly unlikely we’ll see one emerging.

“I don’t yet see Fatah or the security services on the verge of a turning point,” he continued. “But we’re moving in that direction.”

Others point to the dwindling faith https://mendapatkankol.com in Palestinian politics to provide peace, a state, or just a better life.

“If we had anything on the political agenda, things could go quiet,” Raed Debiy told me. “But I’m not sure with this right-wing [Israeli] government whether there is anything solid on the table – so the only scenario I see is explosion. It’s just a matter of time.”